|

Basic Small Engine Repair

Note:

This page is, for now, not much more than a collection of notes. If you have questions or suggestions for this page, feel free to email me. If you haven't done so, you should read the Basic Small Engine Repair page. It's an introduction to small engines and covers many of the things that apply to 2-stroke engines (which will be covered on this page).

Overview:

There are quite a few differences in the operation of 2-stroke engines compared to 4-stroke engines (which were covered on the Basic Small Engine Repair page). The main difference (from a basic repair standpoint) is the carburetor setup. You'll see a common 2-stroke carburetor later on this page.

Hard to Start Engines:

When working with 2-stroke engines, you should understand that they're easy to flood and a flooded 2-stroke is harder to start than a flooded 4-stroke. The best thing to do is to prevent flooding it. It's also important to understand that a cold engine and a hot engine may require a different procedure to start the engine. If the piece of equipment is yours, learn how to start it under various conditions and it will be much more pleasant to own/use. If you're borrowing it, ask the owner how to start it. If he has problems starting it, look up the owner's manual for it. It should provide the best starting procedure.

For most 2-stroke engines, you set the engine shut-off switch to 'run'. You choke it and pull it until you hear it 'pop' (a sharper sound than it initially makes). As soon as you hear it pop (try to start), immediately take it off of choke and pull it a few more times. If the engine is in good working order, it should start after only a few more pulls. If you continue to pull one it with it on choke, it will flood and you will either have to let it sit for 30 minutes (or more) or take the plug out, dry/clean it, pull it many times to clear the fuel in the cylinder and then reassemble it to start it. Hard-starting is one of the biggest problems/complaints with 2-stroke engines. The problem is often the procedure, not the engine.

Pay Attention to Details:

When working on anything, it's important to pay attention to small details. It's the same with rebuilding these carburetors. For example, there will be gaskets to form a tight seal the around the various openings. In some instances, there will be a gasket and a diaphragm. When you pull the components apart, notice whether the gasket is on the body of the carburetor or on the cover plate. For the two diaphragms in the carburetor used as an example here, the gasket for the metering diaphragm goes between the diaphragm and the body of the carburetor. On the other side of the carburetor, the fuel pump diaphragm must lay flat against the body of the carburetor to work properly. If you were to put the gasket between the fuel pump diaphragm and the body of the carburetor, the engine would not run.

Fuel:

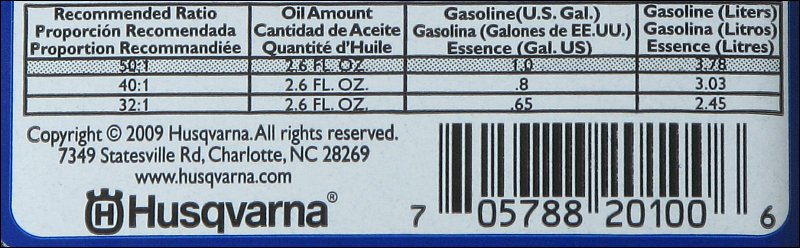

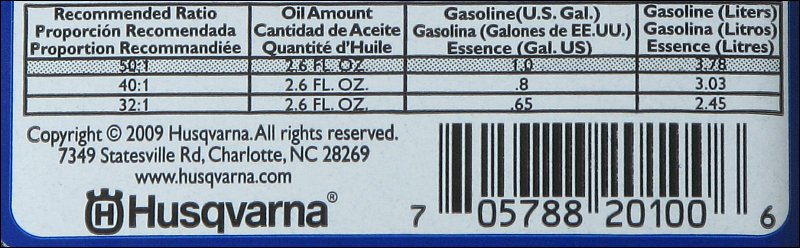

Most 2-stroke engines require that you mix the fuel with a special oil. In most small 2-stroke engines (like those for string-trimmers and chainsaws) the oil is mixed with the gasoline. In larger engines, the fuel is injected into the engine. This oil is required to lubricate the engine. In 4-stroke engines, the lubricating oil is in the crankcase. In most small 2-stroke engines, there is no crankcase oil. When you mix the fuel and oil, you must do so with the proper ratio. Not all engines require the same ratio. If you have engines that require different ratios, you should have separate gas cans, each one labeled with either the mix ratio or the piece or equipment that it's to be used with. The following is the label from the back of a bottle of Husqvarna 2-stroke oil. You pour the entire 2.6 ounce bottle of oil into the amount of fuel listed to produce the ratio listed.

Fuel Lines:

In two stroke engines, there are two very common problems for engines more than about 5 years old. The first is the simplest, a broken fuel line. This is a simple problem but sometimes getting the correct fuel line and routing it properly can be a bit more difficult. Fortunately, there is a lot of online help. If you search for the model number for the equipment and the term 'fuel line', you find the right size fuel line. If you can't find the information you need and will have to try to locate it yourself, you should realize that the fuel lines have both inner and outer diameters. This is important because some fuel line has to fit precisely. For example, in some chain saws, the fuel line simply passes through a hole in a tank and goes to the fuel filter/weight. The only seal where the fuel line enters the tank is the fit between the line and the opening in the tank. If you use a fuel line that has an outer diameter that doesn't seal well, fuel could leak when using the saw at extreme angles. When you buy fuel line, buy at least 2x as much as you need. Sometimes it's difficult to find just the right path for it (there isn't much free space around the carburetor on small equipment) and you will have to find a different route... after you've cut the fuel line. If you have extra fuel line, store it (and any other small parts) in a sealed container. Ziploc type bags work well because they take up very little additional space after all of the air has been forced from the bag. Keeping them in small containers keeps insects and debris out of the hose so that it can be used later, if needed.

This is one example of a weighted filter used in 2-stroke engines. Many 2-stroke engines are used on equipment that is designed to be used in any orientation (a chainsaw, for example). This means that the fuel could be anywhere in the tank (gravity keeps the fuel in the lowest part of the tank). To keep the fuel line pickup/filter in the fuel at all times, a weighted filter is installed on the end of the fuel line. When you repair an engine that has been improperly stored and the fuel has turned to varnish, you need to replace these filters. When you buy them, you need to make sure that you get one that is designed for the size (inner diameter) of the fuel line that you have. When you cut the fuel line, you need to cut it to a length that will allow the filter to reach any part of the tank. You don't want too much extra fuel line because it could allow the line to kink, stopping the flow of fuel into the carburetor.

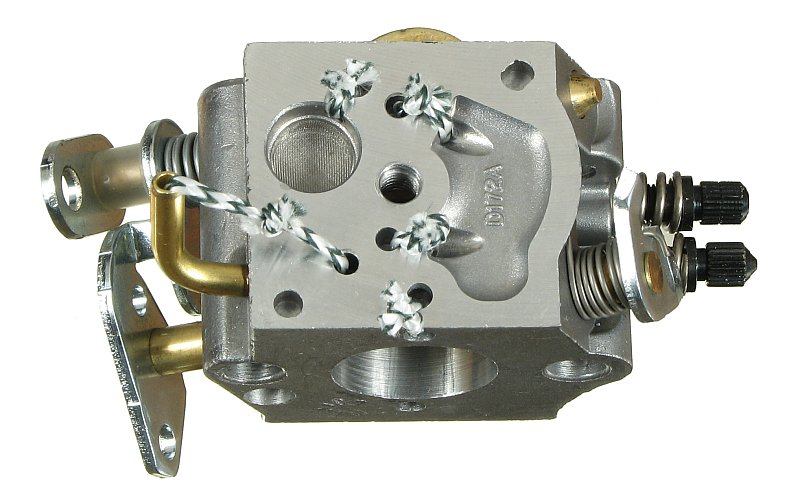

Carburetor Make/Model:

If you're going to buy a carburetor kit and are not going to buy it from the manufacturer, you will need to find the make and model number of the carburetor. Zama and Walbro are common on smaller engines. On larger engines, you'll find Tillotson carburetors also. In the second photo, you see the model for this carburetor. Many times, all you need is the series for the carburetor. For example, this is a WT series carburetor. WA is another series of Walbro carburetors.

Carburetor Kits:

If the carburetor hasn't been rebuilt on your small 2-stroke engine within the last 5 years and you're having trouble with it (hard to start, won't start, has been stored improperly), you should re-build the carburetor. This is not very difficult for someone with a good mechanical aptitude and/or common sense. The kit essentially has everything that can fail in the carburetor. In the photo below, you see the contents of a standard rebuild kit. The kit will likely cover more than one carburetor so there will be parts that you won't use.

Tightening the Screws Evenly:

When working on anything that involves a gasket and a cover-plate that has multiple screws, you need to tighten the screws carefully. When initially installing the screws, only tighten them down to where they're touching the cover plate. After all are touching, start tightening them incrementally. For something like the metering valve cover below, you would start on one corner and then proceed diagonally. Go to the next screw and again go across diagonally. After 2-3 passes, the screws will be tight enough. You don't want to use too much force because it could cause the cover to warp which may make the gasket leak. Don't over-tighten the screws. They need to be good and snug but not overly tight. Do this with a standard (non-battery powered) screwdriver. If you use anything else, you could strip the threads or break the screw off which could mean that you'd have to replace the carburetor.

This page is #11 in the directory.

The Primer Bulb:

On some 2-stroke carburetors, there is a small priming bulb that allows you to create a vacuum much like the engine would to pull fuel into the carburetor. When these collapse or crack, they don't function properly and must be replaced. They are not all the same size so you need to get one specifically for your carburetor.

For engines that do not have an obvious way to prime the carburetor, there may be a 'hidden' priming mechanism. For example, on a chain saw the fuel cap may have an outer o-ring and the cap screws down into a recess. When you screw the cap into the tank, the cap acts like a piston which forces fuel into the carburetor. For these, you may have to completely remove the cap and reinstall it several times if the engine hasn't been used for some time. Each time, more fuel is forced into the carburetor.

If it's a chainsaw that you're trying to get up and running to cut firewood or a downed tree, chapter 23 of this site may be of interest. If there is no directory to the right of this page, go to chapter 23 after clicking HERE. If there is a directory to the right, simply click HERE. If you're proficient in the use of a chainsaw and have time to give the page a quick run-through, please let me know if you find any errors or safety issues. There is a link to my email at the top of the chainsaw page.

The Metering Valve Diaphragm:

The second common problem is the diaphragm. These diaphragms harden with age. Beyond about 5 years, they generally need to be replaced. The diaphragm that you see below actuates the metering valve. When there is a vacuum, the diaphragm is pulled inward and the post on the diaphragm pushes on the metering valve lever. When the lever is depressed, it opens the valve and allows fuel to flow into the carburetor. When these diaphragms are new, they are very flexible. As they age, they become stiffer and can no longer actuate the lever and valve properly. When this happens, the engine typically runs only when partially choked. In many instances, this is the only part that needs to be replaced. However, if you have the entire kit, you may as well replace the rest of the components as well.

Strange problem... A chainsaw I was using had a bad diaphragm but I didn't know it. I replaced the air filter because it was so plugged that it didn't appear that sufficient air could flow through it. After replacing the air filter, the saw simply would not run. If the old air filter was reinstalled, it ran well (but was hard to start). With the clogged filter, the vacuum in the carburetor was greater and allowed the diaphragm to actuate the metering valve. With the free-flowing filter, there was insufficient vacuum to actuate the valve. Replacing the diaphragm solved the problem.

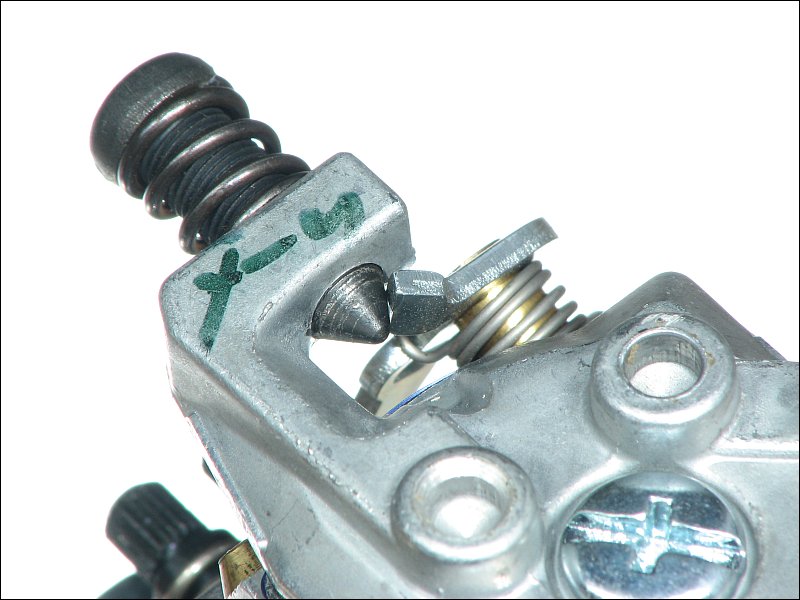

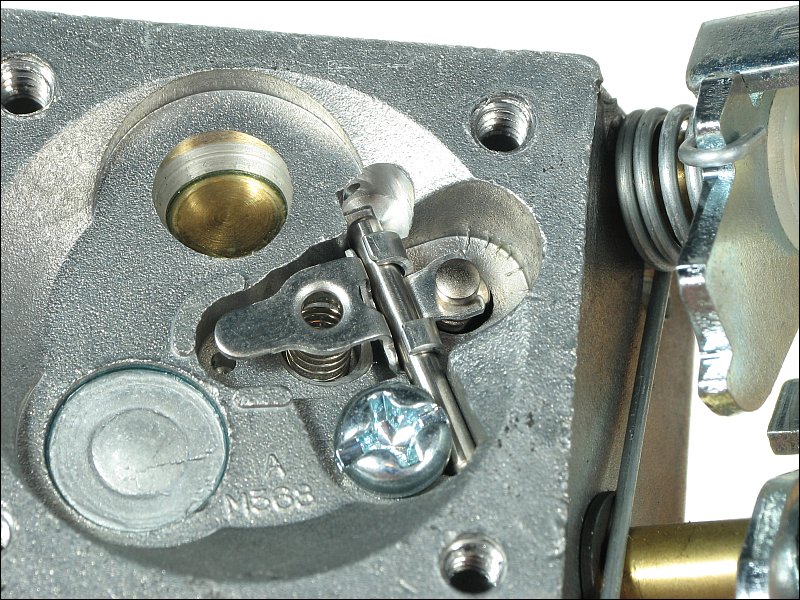

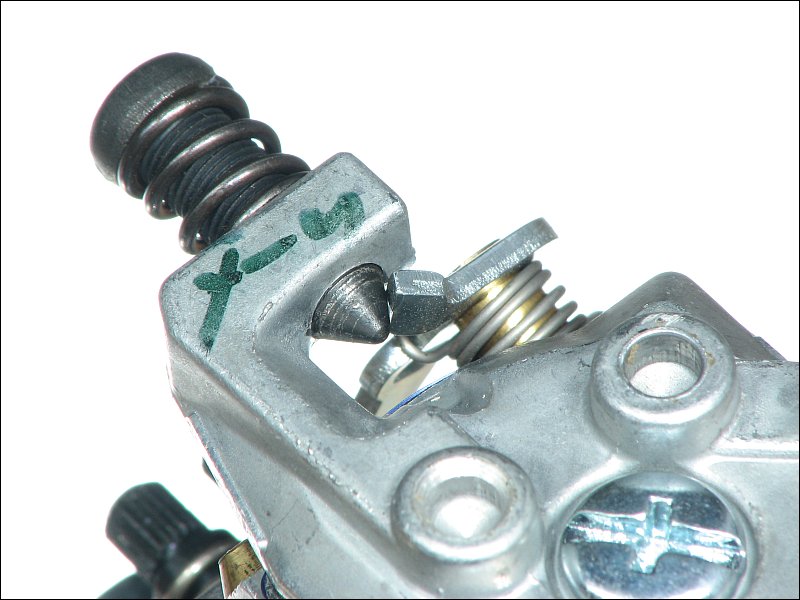

Metering Valve Assembly:

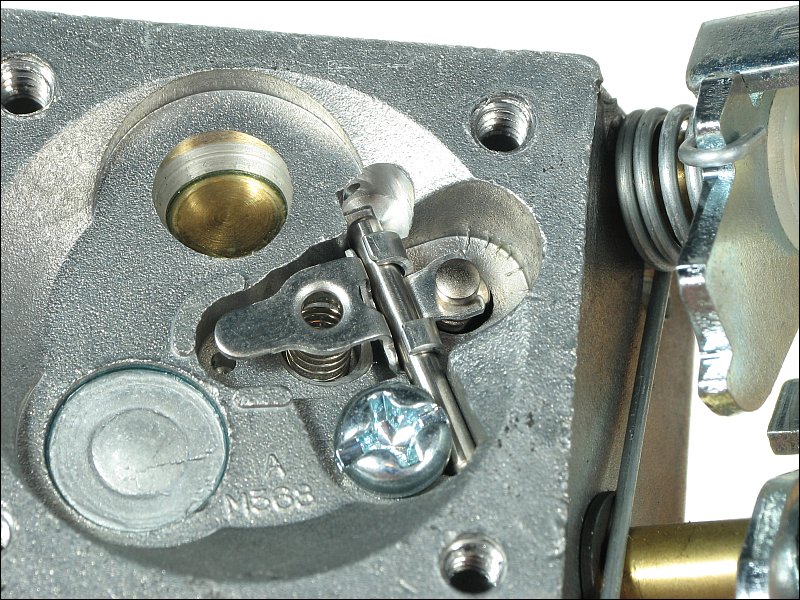

The photo below shows the metering valve assembly. This should operate smoothly and consistently. The metering valve is in the fork of the lever and goes down into the body of the carburetor. The lever is operated by the metering diaphragm. To remove the assembly, you remove the screw that holds the shaft in place. Be careful not to loose the spring. It's not included with most kits.

The round gray component in the image above is a 'Welch' plug. If a carburetor is extremely gummed up, it may be necessary to clean out the idle ports. The only way to properly clean them is to break this plug out and clean the area behind it. You'll need a replacement so don't break the plug out if you don't have a replacement. If you think this area will be dirty, you can order a kit that includes the Welch plugs.

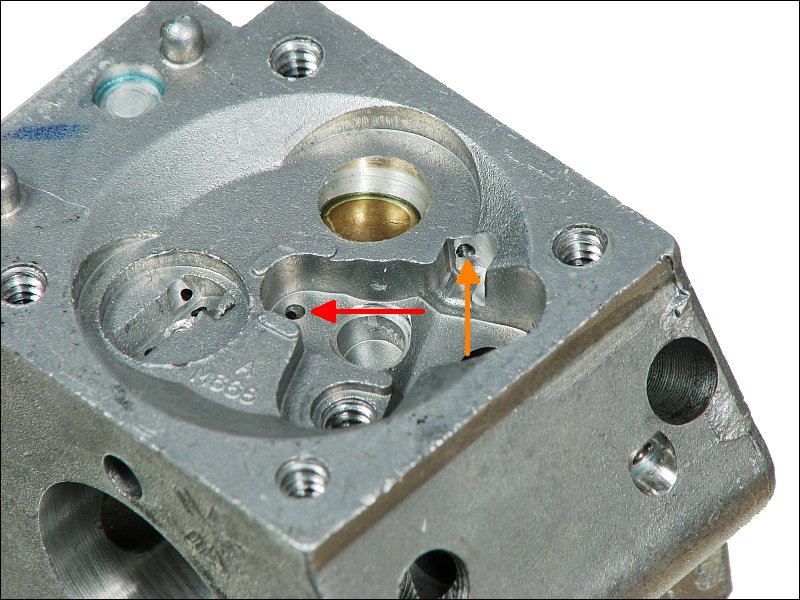

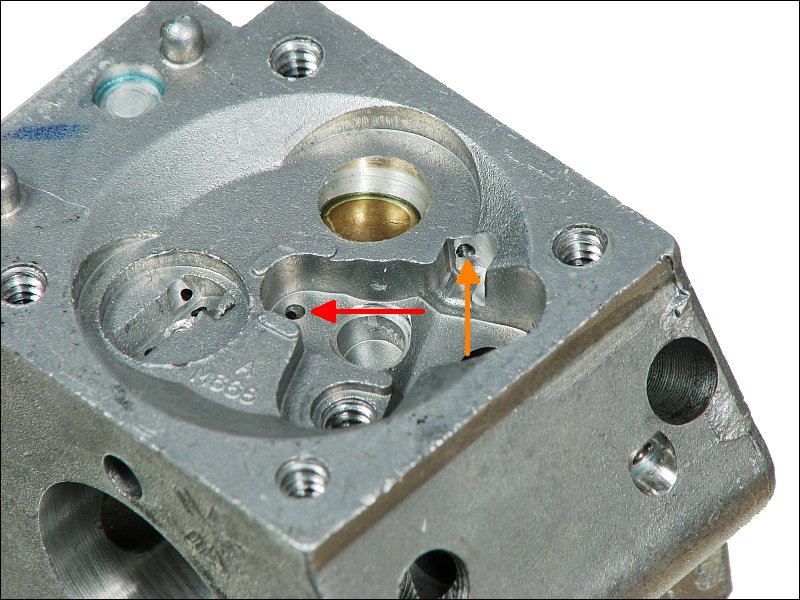

The orange arrow in the next photo shows you the port that allows the fuel to flow from the metering chamber to the high-speed jet. The red arrow points to the port that allows fuel to flow to the low-speed jet.

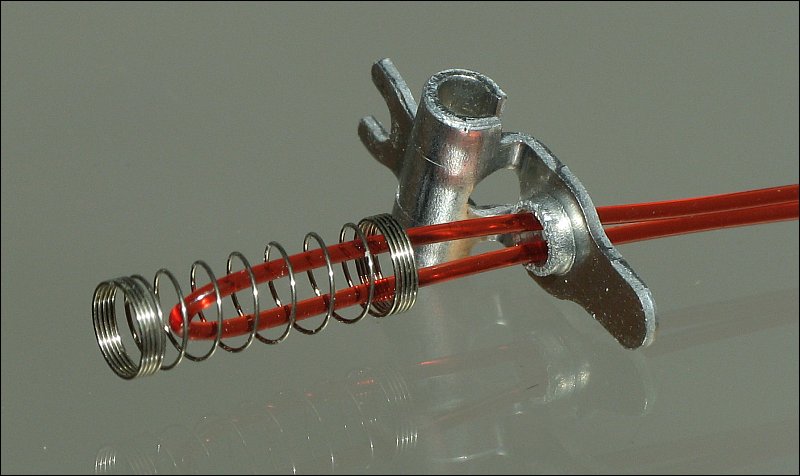

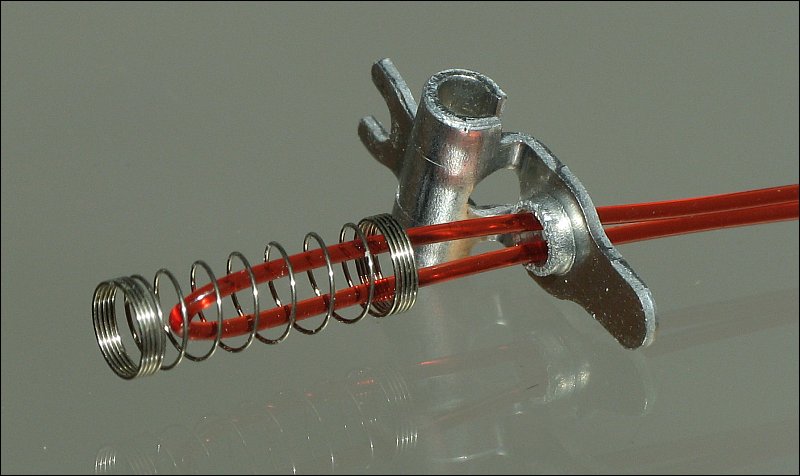

The return spring for the metering lever can be difficult to work with, especially if you have big fingers. If you take a length of monofilament fishing line make a loop in it then insert it through the hole in the lever and then into the spring, the spring won't be so difficult to work with. You can also insert the loop through the hole in the lever when disassembling the metering valve assembly to help the lever and spring together. Heavier line works a bit better because it doesn't pull out as easily. Line that's easier to see is easier to work with. This is 30lb test Red Lightnin' line by Zebco.

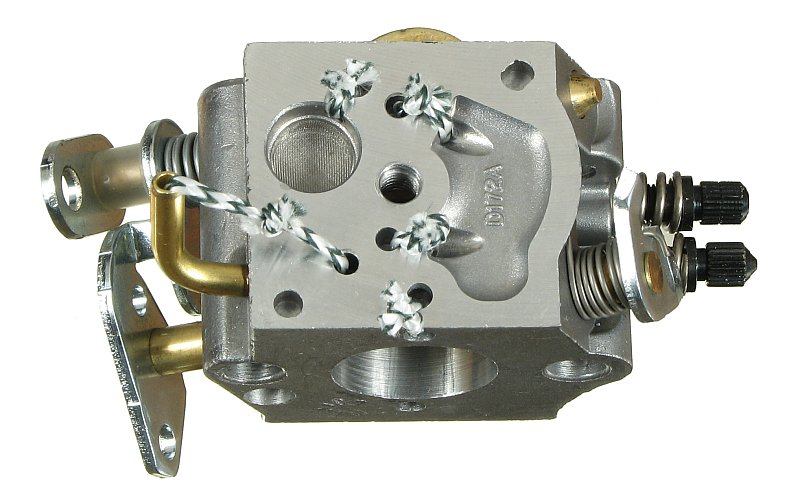

Fuel Pump:

The following image shows the fuel pump assembly. THIS is what the carburetor looks like before removing the cover. The main component of the fuel pump is the diaphragm. It contains the reed valves that act as check valves to force the fuel to flow in one direction. The fuel pump is actuated by pulses of air from the engine crankcase. The port 'W' is where the carburetor mates to the port in the head. It's ported to 'X'. When the fuel pump cover is in place, it mates to the 'X' that you see on the cover. Air pulses pass to 'Y' through the fuel pump cover. That causes the diaphragm to pulse which actuates the fuel pump reed valves. The fuel path is shown in red and progresses in order. The points with the same letter on the cover and on the body of the carburetor are mated when the cover is in place.

Click HERE to make this applet fill this window.

Note:

The image above is a Flash graphic. You can right-click on it and select 'zoom in' from the dialog box. Drag the image with the left mouse button to navigate when zoomed in.

This image has Dacron fishing line through all of the passages in the body of the carburetor to show you which ones are connected. All of these passages as well as the fuel filter must be clean and free of varnish. If any trash gets under either of the fuel pump reed valves, they will not function properly and the engine will not run.

High and Low Speed Jets:

On some 2-cycle carburetors, you will have two adjustable jets. One is for high-speed operation and one is for low-speed (idle) operation. These are typically marked. Below, you can see the markings on the body of the carburetor. On some engines, the adjusters are different colors (blue for low-speed, red for high-speed). This is a generic replacement carburetor and has no slot in the jet shaft. This type of adjuster is designed to have a plastic cap pressed onto it. If you're replacing your old carburetor, you will need to transfer them from the old carburetor to the new one. If they are cracked, you will need to replace them. The plastic caps will likely have to be purchased from the manufacturer since they have to fit into the housing/casing around the carburetor.

Adjusting the Carburetor:

Adjusting the idle and high-speed jets. When adjusting these jets, you need to start with the idle jet. Generally the manufacturer (or other online sources) give you the recommended starting point (tighten until the needle touches the seat then back it out x number of turns). When you do this, don't use any significant force when closing the jet down. You can cut a groove in the needle and damage the seat. After getting the idle jet set so that it will idle smoothly (or will at least run well enough so that it doesn't stall), you can move to the high-speed jet. You will increase the speed of the engine and adjust the jet. Turn it one way then the other to get the smoothest operation. Continue doing this until the engine runs smoothly at the highest speed that it's designed to operate.

Running an engine lean can lead to destroying an engine. It may be counter-intuitive but restricting the fuel too much can cause the piston and head to run hotter than if there is too much fuel. When you are at the point of being too rich or too lean, the engine will rev higher (lean) or begin to run rough (rich). It's better to set the carburetor to be very slightly rich than slightly lean.

Idle Speed Adjustment:

As you get the idle jet adjusted, you may want to adjust the idle speed. The idle speed adjustment is much like it was on the 4-cycle carburetor. It simply holds the throttle open slightly. The idle speeds isn't critical, generally. You want to set it at just about the engine will continue to run without stalling. Setting it higher isn't a significant problem, generally, unless the engine is on cutting equipment that has a centrifugal clutch. For chainsaws and line trimmers, the cutting components won't operate at low engine speeds. The clutch requires fairly high engine speed to engage. If the idle is set too high on something like a chainsaw, it may allow the chain to be driven when the saw is at idle. This can be dangerous.

Choke and Throttle Linkage Connections:

In the following image, you can see the levers that connect to the choke and throttle linkage. The choke lever (A) has a latch that locks onto the throttle linkage (C) when the choke engaged. This holds the choke plate (B) closed. It also forces the throttle open a bit more than it would be normally (at idle). On this carburetor, the choke is automatically disengaged when the throttle is opened to rev the engine.

Back to the Top

|